The 150-year-old technology that could save the planet and your bills.

The heating industry is entering a new era; the Heat Pump era.

Heat Pumps are not new to the heating industry- While the technology was developed over 150 years ago, heat pumps have been relatively absent from the household heating market in favour of gas boilers. This has been due to natural gas being a much cheaper and more reliable option.

However, as the global climate crisis forces us to find cleaner, sustainable sources of energy and the ongoing war in Ukraine continues to affect gas supplies and prices, the humble heat pump is moving up the popularity rank.

What is a heat pump?

A heat pump is a device that uses electricity to bring heat energy from outside the home to inside. Different heat pumps use different methods of collecting and transporting heat energy. For example, air source heat pumps and ground source heat pumps shown in the images below.

Air source heat pump: Fans sit outside the building and circulate outdoor warm air into the heat pump.

Ground source heat pump: A heat-absorbent fluid is run through underground pipes to absorb heat from the earth and transport it back to the heat pump.

What happens inside a heat pump?

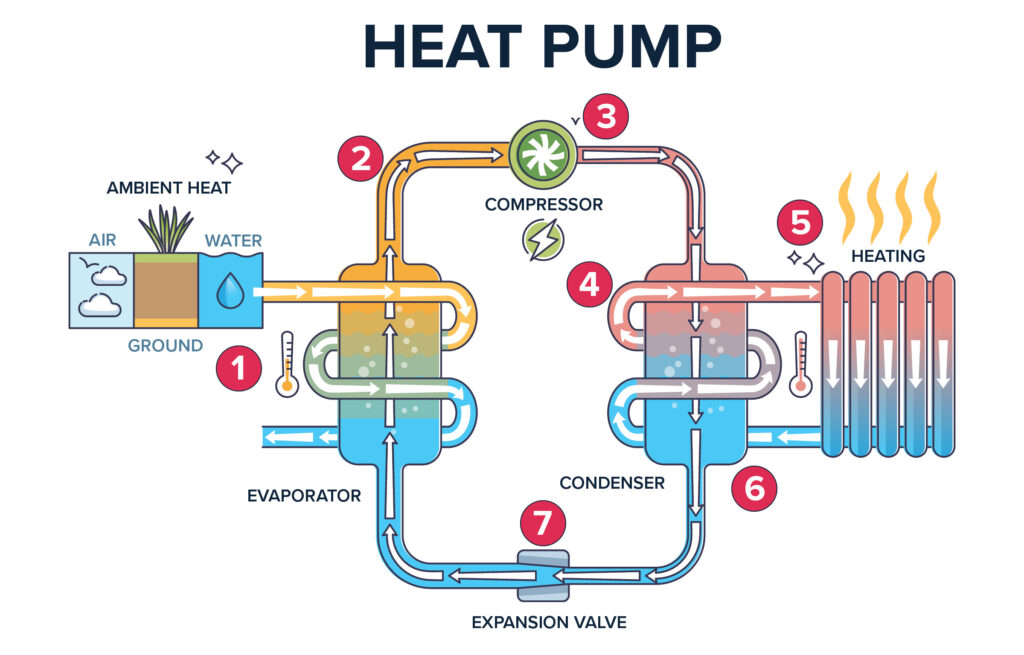

Once inside the heat pump, energy from the source is converted to heat that can warm or cool buildings as shown in the steps on the ‘Heat Pump’ infographic below.

- The heat energy warms a liquid chemical called refrigerant.

- As the refrigerant gets warmer, it evaporates into a gas.

- The gas is then compressed, increasing its pressure and temperature.

- The hot gas flows through a coil that is wrapped around the water tank and heats the water.

- The warm water can be moved through radiators and underfloor pipes around the building to heat the home, a bit like how gas central heating works now.

- As the refrigerant loses heat from warming the water, it cools down and changes back into a liquid.

- The refrigerant goes through the expansion valve to depressurise and cool even further before it moves back to the evaporator to start the process again.

The good thing about heat pumps is they can still gather heat energy even if it’s very cold outside. Heat energy still exists on cold days, and these pumps are effective at collecting it!

Why now after 150 years?

In 2022, around one-third of carbon emissions in the UK were attributed to heating, with 17% of these coming from homes. In our efforts to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050, it’s key that we find cleaner ways to heat our buildings. Heat pumps could be one part of the solution as they’re powered by electricity and can be generated by renewable sources like wind and solar. The Climate Change Committee (CCC) says that heating will need to come from low-carbon sources, and a huge 52% of this will be achieved using heat pumps!

The Russia-Ukraine war disrupted the worldwide supply of natural gas, resulting in a global energy crisis. Here in the UK, we saw our energy bills increase 54% and heard warnings of possible blackouts during our colder months. The energy crisis has forced the UK to consider how the country could become more self-reliant when it comes to energy supply. One of the possible solutions for this is to electrify the energy grid, including swapping gas boilers for heat pumps.

Can we change how we heat our homes?

Changing how we heat our homes isn’t an immediate switch from one to another, it requires thought about how we transition away from gas boilers in current buildings and how we build and insulate homes going forward. Heat pumps could be connected to radiators that are already in homes and in most cases, an air-source heat pump could replace gas boiler systems, however, the radiators wouldn’t get as hot as they would if heated by gas or oil. There is also work to be done to improve our current insulation as heat pumps are most effective and able to retain more heat if a building is well insulated.

Whilst heat pumps are not a direct solution to gas boilers, they may play a key role in ensuring the price and supply stability of our future heating.